Announcements

- Home /

- Announcements /

- Home cooks guide to squash

Home Cook’s Guide to Squash

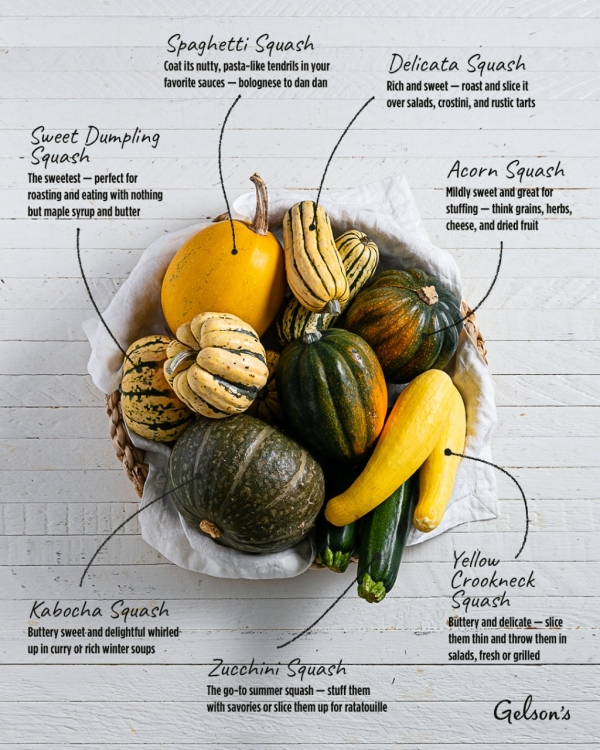

Winter squash, summer squash, we love them all. Maybe too much: the more colorful, gourd-y, and ugly-cute winter squash look so pretty piled in a basket or casually strewn across a table runner, it’s tempting to keep them as pets rather than eat them.

If only they weren’t so darn delicious — and so useful in the kitchen. Squash, in all their variety, are among those veggies (well, technically fruit!) that are so tasty, they really need little to no seasoning. There’s something so summery about a ribbon of zucchini grilled with only a sprinkle of salt and pepper. And a sweet delicata, eaten straight out of the oven with nothing on it, is the definition of winter comfort food.

Yet they’re so fun to dress up: Tossed with aromatic baking spices, squash can be sweet — think rich, creamy pies, moist quick breads, and the wonderful Thanksgiving mashes that are half side dish, half dessert. And they’re also wonderful stuffed with grains and meat, coated in a hot, sweet glaze and grilled, sliced over salads, whirled into a colorful curried soup, and so many, many other savory applications.

For the armchair food anthropologists among us, squash also have interesting provenances — some of the varieties listed here are among North and South America’s native fruits, and others came from Europe and Asia originally. As grocers, it’s thrilling to see new squash varieties find their way into our produce section and gain popularity, some of them heirlooms that we’d stopped farming or once used for decoration only.

In that spirit, we’ve put a sampling of the squash we carry in this guide — the familiar favorites, plus a couple varieties you may not have tried yet.

Spaghetti Squash

Spaghetti squash don’t show up in written histories until 1850 — in China — but squash historians (yes, that’s a thing) believe they were actually native to the Americas and that early explorers carried them to China. They didn’t come back to this continent until the 1930s, when Sakata Seed, a Japanese company, started wholesaling their seeds, and even then they weren’t a huge hit — at least not at first.

Spaghetti squash had a brief moment of fame in the victory gardens of World War II when processed foods were hard to come by, but then they all but disappeared again. Sakata Seed reintroduced them in the 1960s, which turned out to be perfect timing — it was the dawning of the counterculture movement, and California’s back-to-the-landers would soon embrace spaghetti squash as a great alternative to pasta. Now, of course, they’re the darling of gluten-free and low-carb dining.

Spaghetti squash have a pleasing shape and a smooth, yellow skin — that can be a bit of a bear to cut through, so make sure your knife is sharp and the cutting board is secure. The real fun comes in cooking them: in the oven, the flesh separates into long strings that closely resemble spaghetti. They have a tender, slightly al dente texture and a mild, nutty flavor.

As our hippie forebears knew, spaghetti squash are super versatile: We like to pull the tendrils out of the shells and use them in a frittata or a green salad. And, of course, they’re great coated in everything from peanutty dan dan sauce to a luxe plant-protein Bolognese (or a meaty one) or a simple, no-cook tomato sauce. Not feeling the alt-pasta vibe? Stuff the shells with hearty fillings, like white beans and fennel sausage or cheese and broccoli.

Delicata Squash

In the test kitchen, delicata are our go-to squash. Why? Oh, let us tell you all the reasons. First of all, their yellow-and-green skins are super easy to slice, edible, and soft when cooked, so there’s no need to remove them. Second, they have a wonderfully rich, sweet flavor, oddly reminiscent of sweet corn. And last but not least, they have a good story.

Delicata squash are kind of the culinary comeback kid: They were introduced in New York in the 1890s and were wildly popular (of course!) until the Great Depression, when they fell out of favor — they were vulnerable to disease, produced low yields, and didn’t keep as long as other varieties. But, in the 1990s, agriculturalists at Cornell University bred heartier delicatas with award-winning yields and flavor. These blue-ribbon squash are now a favorite the world over. Go delicata!

We use delicata in all kinds of dishes. They’re terrific roasted and sliced over a hearty salad of leafy greens and wheat berries. Their velvety texture and sweet flavors marry well with cheese — try them with goat cheese on our autumnal crostini (think nuts and sweet-tart persimmons) or with Gruyere in the world's most Instagrammable tart. And, if you’re looking for something more hearty and dinner-ish, delicata are amazing coated in gochujang sauce or tossed on a sheet pan with some salmon, cauliflower, and red onion.

Green Acorn Squash

Green acorn squash are an old variety, originally cultivated by Native American tribes. In fact, along with other squash, maize, and beans, they’re one of the staple crops, known as the “Three Sisters” that make up the foundation of the Native American diet. They have dark green skins and bright orange flesh, and they’re mildly sweet and nutty. And just like delicata, they have tender, flavorful skins, so you don’t need to peel them.

Because they’re fun-size, acorn squash are a natural for stuffing — the perfect single serving, and a very pretty presentation to boot. We like them with grains, herbs, greens, fruit, and a nice salty cheese, like feta, but you can really fill them with anything. These little guys can also be roasted and tossed with salad greens or noodles. Pasta Alfredo? Do it!

Acorn squash are so mild, they’re also our choice for recipes that swing sweeter. They’re lovely in maple syrup, or our favorite, the three Bs — butter, brown sugar, and bourbon.

Yellow Crookneck Squash

We love these summer squash for their sunny color, long, swan-like necks, and mild, buttery flavor. They’re also among the older American squash varieties.

Crookneck squash made their first written appearance in Thomas Jefferson’s gardening books of 1807, but they were already an heirloom variety by that time. They were among crops that early Native Americans grew. In fact, scientists once thought they were indiginous to Mexico, but fairly recent genetic and archeological studies show that summer squash may have originated in eastern North America thousands of years ago.

Crooknecks are so similar to zucchini, they can be used interchangeably — raw or cooked. In the test kitchen, we like them julienned in a fresh, slaw-like salad with herbs, feta, and a bright dressing. They’re also brilliant on the grill: try slathering them in a glaze (honey, vinegar, soy sauce, and garlic) so they caramelize a little. And of course, crooknecks are great chopped up in everything from a Mediterranean quinoa salad to a classic game day chili.

Zucchini Squash

According to squash historians, zucchini trace their origins to a 1901 seed pamphlet from Milan, Italy, in which they’re listed as — read it out loud, with a proper lilt please — zucca quarantine vera nana. They didn’t make their way to America until after World War I, but today, zucchini are definitely the most popular of the summer squashes.

It’s easy to see why. They have a mildly sweet flavor that pairs with almost anything. Like their winter pals, zucchini are great stuffed. (Think: mushrooms, garlic, wine, thyme, and a cheesy, breaded topping.) For a light dinner, we’ll cut them into ribbons, grill them, and toss them with pesto and white beans. They’re also classic in dishes like one-skillet chicken and ratatouille or zucchini fritters dipped in yogurt flavored with garlic and Gelson’s Za’atar Seasoning.

And, at the end of the summer, when we’re desperate to unload some zucchini, we’ll hide them in loaf after loaf of zucchini bread.

Kabocha Squash

Kabocha is another squash variety that likely originated in the Americas, but made a new life for itself when early Portuguese explorers carried it to Japan in the 1700s. There, they’re known by a few names, including haku haku and kuri kabocha, which translates to nutty pumpkin.

Kabocha are squat, green squash with a soft skin (no peeling needed!), a dry, starchy texture, and a delightful flavor — nutty with a rich, buttery sweetness. They’re a winter staple, and some home cooks use them to make sweet, immune-boosting soups that help keep colds at bay.

In the test kitchen, we’ve used kabocha to make a rich, ginger-forward miso squash soup. We don’t know if they’re curative, but they’re definitely warming and full of zinc and vitamins A and C. They were also deeply comforting in a recent curry dinner — buttery squash simmered in red coconut curry and served over rice. Of course, they’d also be delicious roasted (go sweet and spicy!), stuffed with a savory rice pilaf, or simply baked and drizzled with maple syrup.

Sweet Dumpling

In relative terms, these little cuties are new to the squash family. Sakata Seed introduced them in 1976, having bred them to be small enough for Japanese home gardens. As fate and poor marketing would have it, they came to the U.S. with the unfortunate name “vegetable gourd,” and because of their small, squat shape and festive yellow and green stripes, were mistaken by the eating public for a purely decorative variety.

Of course, as soon as they were renamed “sweet dumpling squash,” they became a squashy fan favorite. What’s in a name? Everything! Well, that’s not entirely true. There’s a lot to these superlative little squash: Their flesh is as dense and velvety and honey-sweet as a sweet potato. And they have a soft skin, so you don’t have to peel them, which is always a bonus.

Use sweet dumplings anywhere you’d use a sweeter winter squash. They pair really well with spice, so we like to slice them up, toss them with honey, soy sauce, and Sriracha, and roast them — add tofu, and you’ve got a great rice bowl. They’re definitely the one to mash up in a pie. And because they’re so compact, they’re also wonderful stuffed with grains: go sweet with cinnamon, quinoa, nuts, and dates, or savory with leeks, herbs, and wild rice.